January 18, 2013

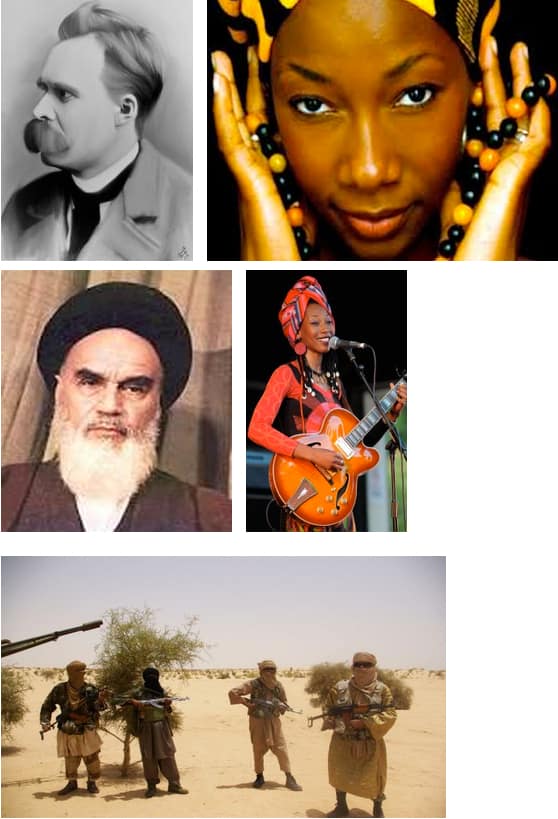

Without music, life would be a mistake.

~-Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols

Why They Hate Music?

When the Ayatollah Khomeini seized power in Iran in 1979, he said the following:

“Music is no different than opium. Music affects the human mind in a way that makes people think of nothing but music and sensual matters. Music is a treason to the country, a treason to our youth, and we should cut out all this music and replace it with something instructive.”

Why do the religious extremists and dictators have such animus toward music? We saw the Taliban forbid music in Afghanistan, dictators like Stalin send musicians to the gulag, Chile’s Pinochet kill nueva cancion (new song movement that championed human rights) artists like Victor Jara, and Argentine generals who threatened the famous singer Mercedes Sosa with death and force her into exile. Ditto for Brazil during the 1960s and 1970s. Ditto for South Africa under apartheid, where black music was censored and forbade any political or social messages. Black musicians got past government censors by writing songs with metaphorical content, often fables about animals. They got their message across to the oppressed black majority. Right-wing religious zealots did it in America when rock and roll hit in the 1950s. The same irrational folks that continue to deny and condemn evolution, science, and art.

Why is music so threatening and dangerous? It is because it celebrates human freedom of expression, of liberty and joy. It’s a slippery thing that generals and theocrats need to control and get rid of.

Now Al Qaeda followers in the Islamic Maghreb, the jihadist’s official name, are in Mali and have forbidden all music except that which underscores Koranic verse. Mali has such deep musical roots, such great traditions and artists. Their music has been celebrated by Ry Cooder, Bonnie Raitt, Béla Fleck (remember his instrument, the banjo, originated in Mali), Northern Tuareg super groups like Tinariwen and Terakaft have already been silenced.

Other Malian artists are worried. Malian music has been paralyzed by the Islamic extremists. Or has it?

Fatoumata Diawara, who has a new CD out on World Circuit Records, was in New York when the violence erupted and has started a campaign for Peace and the Emancipation of Women in Mali. With her new CD she joins an amazing group of top female singers: Oumou Sangare, Rokia Traore, Sali and Coumba Sidibe, and others who have planted the seeds of Malian music and culture around the world. We all know what happens to women when sharia law is applied by the Islamists.

Marco Werman, a host of the excellent program The World on Public Radio International and the BBC, recently interviewed Fatoumata during her visit to New York. a link to Marco Werman’s feature on her on PRI’s The World 1/15/13 http://www.theworld.org/2013/01/fatoumata-diawara-sings-for-peace-and-the-emancipation-of-women-in-mali/ . Fatoumata Diawara says Malian citizens are scared. This is taken from that radio broadcast on January 15, 2013:

“We knew there was a new Islamist group in Mali, but I think that we’ve only realized how serious the situation is for a couple of days now,”

Diawara says. “Things have really changed; the energy of people in Bamako has changed. And since in Africa, men always fare better than women,

my worry was that men would let this situation unfold and let this new Islamist group get to the north and would collaborate with them, because

what this group stands for wouldn’t impact men much, but it would affect women tremendously.”

And, as Diawara told me, it’s not as if Mali’s women have their own spokesperson to talk to the Islamist

fighters. With their political system all but collapsed as well, Malians don’t even have non-military role

models to boost their confidence. Which is why many Malians are looking for some guidance from a group of people they respect: the country’s musicians.

“The Malian people look to us,” Diawara says. “They have lost hope in politics. But music has always brought hope in Mali. Music has always been

strong and spiritual, and has had a very important role in the country, so when it comes to the current situation, people are looking up to musicians

for a sense of direction.”

So, for a month prior to coming to New York, Diawara helped spearhead a project in Bamako with some of Mali’s greatest musicians.

The song “Maliko,” brought together artists like kora player Toumani Diabate, guitarist and singer-songwriter Habib Koite, and legendary female vocalist Oumou Sangare.

Diawara told me the song makes two requests: a plea for peace and a plea for the emancipation of women in Mali. Because as she told me earlier, if there

is jihad in their country, men will always be able to strike compromises with other men.

It will be a lot harder for women.

But Diawara says Malians are determined not to see their country conquered by jihadists.

We’ve seen songs for peace recorded before.

It’s hard to say what kind of impact they actually have.

But Diawara believes this song can help.

The song’s lyrics include this line: “Never have I seen such desolation. They want to impose Sharia law on us. Tell the north that our Mali is one nation, indivisible.”

Music is the voice of hope and has more credibility than official messages. Malian music is such a big part of Malian culture–certainly more of us have discovered the culture from its musical messengers than from painting, sculpture and the other arts. As the French and a multinational coalition hits the trenches in Mali, let us hope Malian democracy and the concomitant human freedom and artistic expression can be restored.

Nietzsche was right, by the way.

Tom Schnabel, M.A.

Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

Host of music program on radio for KCRW Sundays noon-2 p.m.

Blogs for KCRW

Author & Music educator, UCLA, SCIARC, currently doing music salons

www.tomschnabel.com